Introduction

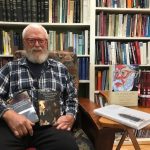

[1] Fritz Oehlschlaeger will be a new voice to many who read the Journal of Lutheran Ethics. A friend and conversation partner of the present writer, Oehlschlaeger is a lay theologian who deserves to be known for reasons I hope to make clear in the course of this essay. In this recent book, he shows how Christian ethics should be telling us about a fundamental, perhaps fatal, dilemma of our civilization: we seek to solve with money and power problems which in the final analysis are matters of love and justice. Money and power to be sure expand human possibilities; Oehlschlaeger’s book is no Luddite brief against innovation, technology or even the market system. Yet money and power do not and cannot make us more loving or just nor can they reconcile conflicting desires to achieve workable social harmonies in real history. For those ancient vices of envy and greed, the money and the power are never enough. They are never enough because they cannot, given the human condition of finitude, secure the phantasm of absolute sovereignty that tacitly is sought under the conditions of secularism. Blinded to our finitude like the rich fool in the parable of Jesus, the blind building of bigger barns only makes us worse and our problems greater. In the thrall of power and money, we forget our common state of ineradicable vulnerability; we forget that the moral right to life is basic and inviolable: “life is the condition on which all other desires depend” (100). As morally basic (whatever its legal status may be), the right to life ought to lend order and direction to all other desires which may be satisfied or frustrated, restrained or indulged in its light. The moral limit of my own desire is that I may not, inasmuch as I wish likewise to be protected, deprive others of this condition on which all other desires depend.

[2] The sad fact that human history honors this most basic moral commitment so haphazardly does not vitiate its necessity. How much worse history would be without its moral force at work shaping and directing desire! How much worse the future will be with the erosion of its force, however unintentional, caused by the current practice of abortion. “If the wrongness of killing lies in a distinctive, exceptionless prohibition against it, we will form our desires in a way that precludes killing.” But relativizing a desire to kill to one inhibition among others that might be chosen across a spectrum of legitimacy “leaves us freer to form desires of sufficient intensity and value (at least to us) to override the wrongness of killing” (101). The victim is social trust, as Oehlschlaeger repeatedly reminds us, which has its sine qua non in the absoluteness of the prohibition of killing. “One thing that is wrong with killing is that it makes rational discussion impossible. Participants in rational conversation must believe that they are not subject to being killed: if they are in need of being reassured on this matter, then the possibility of such conversation has been lost” (304). By contrast, “commitment to the irreplaceability of persons will lead us to creative economic thinking –in a very broad sense—that utilitarianism may not, particularly if it is allowed to put the very existence of individual persons into question” (238). Moral deliberation as a process of reasoning together for the common good presupposes such basic and unconditional acceptance of others in their own bodily integrity, as integral living organism. “Doesn’t the process of becoming just involve learning to respond appropriately to others irrespective, or even in spite, of how one might want them to be or think they should be…?” Oehlschlaeger asks. “Does not our learning to be just depend upon accepting the limits both of others and ourselves and then coming to recognize the achievements or claims of others against the background of common limitations? If human nature comes to be seen as fully alterable, how will one know how to justly recognize another’s due?” (230, emphases added)

[3] Note well: common human “nature” here is being taken not in the sense of philosophical essentialism (see the critique of Aristotle, 82-5), i.e. as the formal possibility and intrinsic imperative to actualize a specific predetermined essence. Rather, human “nature” here means something much more down to earth, namely, the natural condition of somatic existence with resolute awareness of each individual’s genetic singularity, individual particularity and ineradicable mortality. Oehlschlaeger uses the jargon of “species-typical functioning” to establish a natural “base-line” (e.g., 221-2) by which to differentiate therapy from enhancement. This “typicality” includes natural aging and eventual death with life-long exposure to that latter threat coming prematurely. Just because of our ontological condition of vulnerability, we both have and need the right to life in a species-typical way.

[4] As the rhetorical questions above indicate, however, a peculiar new and formidable appearance of the ancient temptation of power and money comes on the scene: the biotechnical. Its allure lies in the prospect of transforming human nature, indeed overcoming ontological vulnerability, and thus radically sidestepping the call to overcome ourselves in the direction of love so that we become just people in just societies. “How will the competing claims of members of different cohorts be adjudicated when there is no longer an assumed background of shared human nature?” (230) Yet that is the biotechnical point: there will then be no need to adjudicate conflicting claims, because “we” will have by eugenic means totally programmed “ourselves” to be happy and sociable. We will have reached a “condition of such abundance” as to make “justice no longer necessary” (192). It is in response to this ominous and fantastical project, made newly plausible by biotechnology, that our author treats the contentious matter of abortion –“the issue that most poisons our political life” (12) – in a new and fresh way.

[5] “I write as a critic of abortion, but not as one who would advocate making abortion illegal” (47). Oehlschlaeger’s extensive engagement with the literature on issues at the beginning of life reflects both Christian theological and philosophical feminist perspectives which he develops in this work. Regarding the latter, there should be no doubt of Oehlschlaeger’s bona fides. He undertakes the burden of showing that “desire to protect the fetus from conception can be consistent with support for the aspirations of women” (14). He regularly unmasks “male ways of thinking that fail to do justice to women’s experience” (38, 80-3). He has pro-lifers ask themselves feminist questions, e.g., whether the ultimate ground of “the strong separation of gender roles” is “that war is necessary, inevitable” (53). He suggests that “feminists are right to attack the enterprise of genetic engineering as male usurpation of reproduction” (179). Oehlschlaeger makes a point of disowning the mere outlawing of abortion as the essential goal of his pro-life position: “women’s need for abortion is directly related to the gender inequality that has marked, and has continued to mark, this and nearly every other human society” (14). Many pages later this initial judgment is reiterated in a surprising concession to Peter Singer. Singer “sees the broad abortion right to be essential to women’s self-determination;” Oehlschlaeger approves in the sense that this “may well be the case under the current economic and social order shaping gender relations” (313). Under the current order, outlawing abortion would subjugate women to unwanted pregnancy, thus depriving them of that personal sovereignty which our kind of society valorizes, just as it would also disadvantage them in economic competition with men. The very possibility of rational persuasion about the morality of abortion under these conditions depends on granting abortion as the social equalizer which it is. But for Oehlschlaeger that tells us far more about the endemic injustices of our kind of society than about the morality of terminating unborn human life.

[6] In tandem with that and writing from the Christian ethical perspective, Oehlschlaeger acknowledges that our convictions about ‘when life begins’ (a separate question, of course, from the morally basic ‘right to life’) rest “on particular perspectives that are bound to the whole personality and can only shift with a reorientation of the person” (quoting John Noonan, 48). Hence, the author’s purpose is not to muster the state to coerce pregnancy under the present order of things but in the realm of culture “to keep the issue open: to resist the conclusion that it has been settled definitely in favor of the justifiability of abortion on demand” (48). Thus the author argues in the hope of reorienting persons, including forming in them the new orientation of the gospel towards the coming order of God. Philosophically, however, Oehlschlaeger also ventures to this end that the most immediate and perhaps even most efficient steps towards “meaningful change” will come “by the transformation of men’s attitudes towards children” (14). That would also entail change in attitudes about work and social status. The entire book may well be read as an effort in such transformation of persons within the post-modern, post-Christendom situation of critical pluralism: “Christians should welcome the freedom made possible by post-modernity: the freedom to make their convictions plain without reliance on the force that inevitably distorts them” (6). I will return to the promise and perils of this posture in conclusion.

Our Brave New World

[7] The precocious fashion in contemporary moral philosophy is to construct little stories dramatizing supposed ethical dilemmas or impasses which the philosopher then gets to analyze for us, no doubt, to our enlightenment. For famous example, Judith Jarvis Thomson told the unlikely story of the “Unconscious Violinist” to liken an unwanted pregnancy to being taken hostage. It seems that the Society of Music Lovers has found that you alone of all people have the right blood type to save a beloved violinist, comatose due to renal failure. So they kidnap and drug you, then plug you into his circulatory system. Now awakening, you learn that to unplug you from the violinist would mean his death. But “Relax,” says the Authority Figure, “his recuperation is projected in just nine months. Then you can be freed” (118). Thomson’s allegory, calculated to elicit our outrage on behalf of the kidnapped, elicited a flurry of expansions and elaborations among moral philosophers, all following her lead to justify elective abortion morally (104-69). But “too often we fail to assess the kinds of narrative choices these stories embody,” Oehlschlaeger observes in the course of dissecting such literarily amateurish ventures, “or to recognize their rhetorical purposes” (108). Such episodes deflect attention away from the cultural and economic order in which the practice of abortion is embedded and which it expresses. Indeed they are constructed, consciously or not, to conceal that order and the sacrifices it requires of us. Thus Oehlschlaeger shows that at the heart of Thomson’s allegory is a false analogy, concealing a presumption: “Unlike the violinist, the fetus has no chance to be just; its sole dependence on another is at once both ordinary and unelected. To abort it is to kill it, in a way that is not true of unplugging the violinist” (or the Society of Music Lovers) who does (do) have a moral choice, a choice to be just, namely, “to let himself die” (to let him die) sadly but naturally rather than unjustly exploit another in order to secure his own life (their favorite violinist’s life, 123). The presumption hidden in the allegory is that being an adult at full powers is normative, that such powerful adults have a socially contextless and unnatural right to extend life at any moral cost, so long as they or their allies have the power to pay for it. What a picture of our affluent false consciousness, the ready rationalization of our power and privilege! As a result, the moral demand of love, as in Jesus’ parable of the Good Samaritan, is rebuked. Adults have the right to be “bad Samaritans” (well, even worse, hostage takers). We never get to see in this parable the most ordinary action of moral life, Christian and otherwise, in daily “giving death” (i.e., frustrating some desires –cf. Romans 8:20– for the sake of others).

[8] In such analyses, Oehlschlaeger unleashes the skills of an accomplished literary critic on “the imagined examples of philosophers to suggest that their narratives also frequently need to be scrutinized as works of fiction” (325) – a designation I italicize, because in the realm of philosophy into which this author treads, “fiction” is a polite way of saying “artificial and tendentious.” As mentioned, such atomistic portraits are created to conceal the function of the current practice of abortion in the late capitalist machinery. In the detailed analyses of this book, a veritable host of progressive moral defenses of abortion or abortion rights (Dworkin, Boonin, Rachel, Steffen, Muller) and their defenses in turn in pragmatist-utilitarian philosophy (Stout) are examined, dissected, weighed and found wanting.

[9] Yet, as already alluded, this book is no ordinary “pro-life” brief. It works to position the practice of abortion, now sliding into eugenics and flirting with the possibility of infanticide, in the spiritual world and subjectivity of which it is part. Can we see ourselves, for example, as a nation “committing itself to a policy of limitless economic expansion in a world of very unequal powers…. [which] would be required, as a minimum, to ensure the dependable, steady flow of inexpensive energy sources; to encourage vast concentrations of corporate power in the name of efficiency…; to convert every available citizen into an economic subject first, at whatever cost to their other roles or identities, and to displace a whole variety of costs –monetary, human, natural—from present to future, i.e., to incur great levels of debt because the imperative of growth is now” (192-3)? Can we see ourselves therefore committed to militarism abroad (134, 139, 291) and the progressive social atomization of the domestic population (193)? Can we in the knowledge class see ourselves as part of an elite grab for social control (197, 212, 218, 224-5, 227), anticipated but not hitherto paralleled on account of the enormous new power made available by the rise of biotechnology? Backing up this self-portrait, can we see at bottom of all this our own very bleak view of the creation: “Each of us is a replaceable ‘object of care,’ a death waiting to happen in a nihilistic world where the best we can do is to continually transfer care from one lost object to another not yet taken” (338-9)? Can we own up to the same elitist logic which led Heinrich Himmler to design the factory-efficient death camps after visiting a gruesome “action” behind the Russian front: “Once the decision to do harm is taken… one ought to do that as painlessly as possible…” (110).

[10] Our practice of abortion, for Oehlschlaeger, is part and parcel of this “sacrificial system” just sketched. Within it the moral justifications of abortion by the philosophers and their theological camp followers function to “sacralize the natural and social investment, the ‘earnest’ expended on each of us in advance… The killing of fetal life works… to impart value to other kinds of choices: getting on with one’s life… redeeming one’s existence. These are now elevated to the condition of sacred responsibilities by the fact that abortion has made them possible” (63-4, i.e., in contrast to “women’s lives being ‘wrecked’ and ‘wasted’ by child-bearing and rearing” 65). Thus today’s parent says to the child: Look how valuable an investment you are, since we did not abort you like others, but chose you, indeed designed you and enhanced you at great cost! The powerful ideology (in the Marxian sense of masking the real economy of things) erected on this elitist base is paradoxically egalitarianism in economic and social pursuit. “To abort is to kill, reluctantly, for the sovereign, to exercise responsibility earnestly in the pursuit, and the currency, of equality” (65) – where “equality” means not the achievement of social solidarity of real existing individuals but equalization, the leveling of all real difference, to make us replaceable parts in the ever-more efficient machine, where, however, some will be “more equal than others,” i.e., the Designers who will decide the conditions of equality for the rest. Such sacrifice for the sake of “equality” is predicated upon the “important, largely concealed fact of political life under pro-choice –that is, that I have not been welcomed into the polity as the being I am most uniquely, for my genetic inheritance partly constitutes that, and it was not enough to give me a claim against being killed” (73).

[11] By the same token, these elitist dynamics of egalitarian ideology cannot consistently stop at merely human equalization but press on against the conceits of “speciesism: the unjustifiable preference for one’s own species” (317). The real target here is the hitherto existing family, with its procreative reproduction by “natural lottery.” Oehlschlaeger takes up Peter Singer’s cogent if noxious argument that there is no principled difference between our practice of abortion and its extension to infanticide (except the emotional investment in a baby by its natural parents), and his further suggestion that such emotional attachments formed in biological parenting are at the root of our prejudicial speciesism. Drawing out the implications of Singer’s argument, Oehlschlaeger muses that enlightened policy ought then to be “directed at breaking down parents’ preferential and exclusivist regard for their own children, at least when they are sub-optimal. Such regard might be the appropriate object of rational therapy… [overcoming the parents’] purely emotional response that ought not to be allowed to exclude the [sub-optimal] child’s replacement” (317). This discounting of emotion as a source of moral insight, of course, comports with the radical Cartesianism of the entire project (311) in fostering the subjectivity of a putatively sovereign self which reigns imperturbably over the body and its passions.

[12] But the slide down the slope from abortion to infanticide is no longer anything to fear. In Singer’s words, “once we are old enough to comprehend the policy, we are too old to be threatened by it” (303). Singer’s own argument is a straightforward call to intellectual clarity and moral honesty about what we are already doing, revealing of the “sacrificial system” of late capitalism: 1) there is no moral difference between abortion and infanticide, 2) since in deciding to have a child, parents in any case decide against having other possible children, and 3) these latter choices should be guided by the utilitarian directive to bring about the greater good (308-9). Ergo, eugenic selections are already being made, which selections should be calculated to bring about the greatest good for the greatest number. Let us then be brave enough to be the sovereign selves that already we are in process of becoming.

The Sovereign Self

[13] The “biomedical imperative” to “eliminate suffering and expand the realm of human choice…, to relieve the human condition of subjection to the whims of fortune and the bonds of necessity,” evokes a sovereign self. This sovereign self exercises in turn “vigilant control over our bodies.” The human body becomes “the object of one’s choices” (5), as if we were “Cartesian angels manipulating a machine” (16). The background narrative is Hobbes’ tale of humans as ‘rising beasts, not fallen angels.’ The state of nature is the chaos of multiple aspirations for security in a world of scarcity; here “life is a necessity that demands what is necessary for its continuance” to be met and limited only “by counter-necessities” (122-3). Aspiration to sovereignty, however, is contradicted by the ineradicable fact of mortality; kings perish and thrones fall. The Leviathan is a mortal god. Contemporary egalitarian ideology does not disown the Hobbesian problematic but democratizes it. To continue with the sovereign self despite this contradiction of the mortality of ineradicably somatic existence, one must somehow overcome death: “our profoundest dilemma as creatures fully cognizant of mortality is that involving our continuity beyond death.”

[14] Contemporary issues of procreative ethics are located by Oehlschlaeger at just this juncture where the self seeking sovereignty must somehow overcome the fatal dissolution of its project. “The simplest, most straightforward approach to that problem would be to shape our children fully in our own images” (320), as cloning technology actually makes thinkable. Short of that, already our current practice of “abortion is one of a series of technologies –the crudest, if you will—whose goal is becoming increasingly transparent: the comprehensive shaping, control, and selection of the kinds of human life we will allow to be” (52), as we heard above. The “situating of abortion choice among other consumer choices” (50), the “replaceablity” of fetuses (314) argued by philosophers morally to justify abortion as a choice alongside other choices actually made in entertaining pregnancy, the parental expectation of return on investment (62) – all this amounts to the “commodification of children” (21). This is a process now underway, bridging a transition from the crudity of abortion to the sophistication of cloned babies, in this way insuring the sovereign self’s virtual immortality.

[15] This analysis leads Oehlschlaeger in the direction of Foucault’s notion (54) of the “biopolitical” nature of the contemporary state (i.e., that the modern nation state is primarily about “distinguishing who can be killed and who cannot” 91): an economic and military order which systematically sacrifices magnitudes of unborn children (and others) to sustain privilege (gender privilege as well as other privileges) in the name of economic necessity which must, in the process, progressively departicularize (= equalize) all persons for purposes of economic efficiency, reducing them into interchangeable cogs in the machine. The irony of this ideology of a coming world of the equality among sovereign selves is massive: the aspirational sovereign self disembodies itself, sheds all historical particularity, levels everything in the name of egalitarianism only itself to be reduced from person to part.

The Narrative Self

[16] In contrast to this sovereign self of late modernity, Oehlschlaeger draws a picture of the narrative self stemming from the Biblical tradition: “unique, embodied beings, each of whom lives out an unrepeatable history experienced from a point-of-view never fully commensurate with that of others…” (13); “the destiny of being on the road between an unchosen conception and an ineluctable death as the uniquely historical beings we are, here once for all only” (70). While the formulations here are sometimes Heideggerian (e.g., 323), the narrative self which Oehlschlaeger depicts is in its fullness the Biblical self, so to speak, ‘being towards death-and-resurrection.’ “Death remains the enemy, but, through the cross, it can come to be seen as a kind of gift, the condition of a love that sees the other truly as an other… so that Christian parents can come to understand their work and joy is not to rear images of themselves but to be, with their children, images of God” (347). If this is not existentialism, it is also not, to repeat, essentialism: “[n]ow curiously, I share the condition of uniqueness with all others” (73). Here what we share with others is the fact of each individual’s uniqueness, each one’s particularity as a unique historical formation; thus we are persons seeking authentic community, not accidental instantiations of the genera Homo sapiens which ought not to deviate from the formal norm (as if this latter idea were somehow more real or authentic than actual individuals!). Such affirmation of the narrative self involves Oehlschlaeger with the Leibnizian idea “that all events in a person’s life are internally related to all the others, such that implicit in a fetus are all the experiences of the adult, and this is due to God’s eternal ‘foreknowledge’ of everything that is to happen” (citing Dombrowski and Deltete, who are attacking Leibniz in order to depersonalize the fetus, 87).

[17] Notwithstanding the complexities of divine foreknowledge, it is clear that if the events of our lives are not internally related, the alternative is that these events are only externally related, fortuitous really, “one damn thing after another” (89) out of which perhaps a good existentialist might “make meaning,” as we say nowadays. Strictly speaking, as a result, we cannot speak of personal identity spanning time (88) in a coherent narrative, but only of the temporary existential connections constructed by the project(s) of the sovereign self – who may in the ultimate expression of sovereignty simply reinvent his or her visible mask as conditions require, forgetting what one has been (as notoriously, the Yale literary critic and former Nazi, Paul De Man, forgot his past). In the latter case, no fetus is the beginning of a particular, irreplaceable person; any one fetus can be replaced by any other, the more so as fetal life is subject to biotechnical design. However less “strictly” than Leibniz a contemporary Christian theologian might take divine foreknowledge, he or she will hold with him that “the continuity of self into the future depends not on us but on the God who sustains the world.” The events of a person’s life therefore are believed to be somehow internally related, unfolding God’s providential purpose by turning good out of evil, since “even the hairs on our heads are numbered.”

[18] More theologically than Leibniz, Oehlschlaeger affirms that “God’s future has come forward in Christ and thus, at baptism, the Christian begins to live proleptically in a future that is at least partially known through Jesus’ cross and resurrection” (89). Thus our “giving death” along life’s way in new lives of self-giving service is grounded and articulated in God’s own self-giving, which master narrative works to make coherent wholes out of the scattered fragments of meaning in life, including the not infrequent betrayals of the new self in Christ: “Because I have been formed to be a person who does not want to kill, I also do not want to let others die when I can prevent that with little risk to myself… what simultaneously nags at me and enables my response [to others who are threatened] is the Christian story’s drawing me into community with those everywhere [and preventing my escape into irresponsibility]… by the story of God’s choosing to die (freely and unnecessarily) for me, and the sure knowledge that I can be forgiven for not regarding myself as wholly responsible for the lives of others.” Otherwise, “I would surely seek to justify myself by referring responsibility away from myself…” (130). Well said. Yet if the Christian so believes in God for him- or herself, then “God’s love for the world” (Bonhoeffer) holds not only for the Christian who is blessed to know and trust this, but for all who have been claimed and won at the Cross. So the baptized Christian would have to hold as true for all others what she or he holds for self: that God has known me “from my mother’s womb.” Every human life is internally related by God’s love for it in Christ, which promises to connect all the dots, in the pattern of Jesus’ cross and resurrection, to create each unique human individual and weave it, together with all others, into the coming of the Beloved Community.

Birth Pangs of the Beloved Community

[19] Thus we come to the enormous contemporary difficulty of the biblical and Christian view of the narrative self: the ownership of pain and suffering which it entails, what ancestors in faith used to call “bearing the cross.” This ownership of the particular suffering body which one is given at and from conception puts the Christian view radically at odds with the “biomedical imperative” of the sovereign self to abolish pain, even at the cost of virtually abolishing bodily existence, as we have seen. Echoing John Paul II’s critique of the sovereign self’s “culture of death,” Oehlschlaeger writes: “Suffering becomes simply a problem to be solved, a scandal that ought not exist, rather than a mystery that must be confronted and lived through in mutual dependence” (20). Rather than the sovereign self’s desperate (i.e., from the Christian perspective, hopeless) reliance on technology to solve our problems, the narrative self’s embrace of suffering unleashes the ethical and social creativity to put technology to better use, i.e. for building communities of love and justice composed of particular individuals. “Suffering itself, the struggle against limits, serves as an important motivation for the creativity that discovers new possibilities for human flourishing” in personal virtue and social justice (262). As per the Leibniz introduced earlier, Oehlschlaeger therefore finds himself defending the created goodness of what Leibniz (too paradoxically) called “natural evil:” i.e., the “evil” that is natural to any conceivable creaturely existence, the “evil” of non-perfection, non-divinity. Hence “there are kinds of suffering we should work to eradicate… but there are other kinds of suffering that we ought not to lessen. I want to protect my child from touching the hot burner on the stove, but when he does touch it, the suffering it causes will him teach him a series of important lessons…” (261). We need just this distinction between natural and moral evil, in other words, to see what evils are wrong and to be resisted or endured, overcome or protested or even accepted in the strange action-passion of self-giving (262). Recalling the opening paragraphs of this essay, we suffer the limit of God’s good commandment: Thou shalt not kill!, in order to find new and better ways to live together.

[20] Needless to say, this counsel strikes even otherwise sympathetic denizens of our brave new world as utopian. It is certainly reflective of an eschatological faith which defers its own reward to the resurrection in order to invite to the feast those who cannot now repay. But in just this way it really touches the present reality in and as the community of faith: “the church must be a community capable of acknowledging and bearing suffering so as to be an alternative to the impossible secular project of banishing all suffering – a project too easily given, in its worship of efficiency, to banishing those who suffer” (286). The primary domain in which Oehlschlaeger envisions the practice of such Christian discipleship is the family. “The free gift of self from parent to child will be, for many, the realest analogy –and pointer to—God’s free gift of himself in Christ” (21). Especially under modern conditions of prolonged life-spans, the “joining of man and woman must now be thought within the context of prolonged commitment to nurturance and education of children – these being no less ‘natural’ and embodied actions than the joining itself” (34), for “marriage is not something whose terms can be invented… it requires the sacrifice of autonomy. They have become ‘one flesh,’ quite literally, in their children” (38). Indeed, parents “have always been vulnerable in their children… one is now at least as endangered and as vulnerable in the life of another as one is in one’s own” (41). Just so, in the joining of marriage, as in the procreation of children, the person is reoriented, the sovereign self is decentered. To “learn to open themselves to increasing vulnerability in one another and their children without anxiously seeking to protect or shape their children’s identities” is to learn love (42) – agapic love which corrects and purifies eros. (How much more the case in adoptive parents, I might add, where your child is not genetically your own; here you either refuse to acknowledge the child fully, or you learn in a much more radical way your charge to be a steward of a little life that is precisely not an extension of your own being.) This focus on the primary community of the Christian family protects Oehlschlaeger from the criticism of utopianism, though it does not protect him, as I shall note in conclusion, from the potential criticism of a Christopher Lasch: that ‘the haven from the heartless world’ has already been penetrated by the monster of the brave new world and is increasingly absorbed by it. In the latter case, the family needs political defense and legal protection.

[21] In any case, as the new subjectivity of faith in divine promise narrated in Christ is at odds with “the things that are,” we are led to a very different relation to the secular state than we have seen with the sovereign self: “To be a critic of abortion, then, might be simply to insist that I want to be received into society just as I am and that I cannot be just as I am so long as the state accords me protected status only insofar as I assent to its definitions of who can be killed and when” (91). The cost of such resistance is “learning to give our deaths” (347), just as ancient martyrs knew. So the church must not only be an alternative community of care, a colony of God’s future within the official world of the contemporary secular state; that could end up as little more than chaplaincy, reinforcing this status quo. To resist, the community of the self narrated in Christ must also become again the church of “Christian liberty.”

[22] Supporters of the current practice of abortion with their tacit Enlightenment commitments to the sole sovereignty of the secular state (as in, “Don’t impose your religion on me!”) suppose that “to hold a belief is to work for its institution as law and thereby to force it on others” (59). They do not know nor can they imagine “Christian liberty,” the Pauline “freedom for which Christ has set us free” (Gal. 5:1). This is not their kind of freedom, the freedom to be a “bad Samaritan,” the concocted freedom of consumer choice in reality much manipulated by moneyed purveyors of bread and circuses. It is the freedom in Christ to “bear one another’s burdens” and to “return good for evil,” as in, concretely, bearing and nurturing unplanned, unwanted, even forced conception. Such Christian liberty does not imply, Oehlschlaeger hastens to add, that the victim of rape or incest returns “evil for evil” if she chooses to abort; rather “she defends herself against the evil perpetrated against her.” At the same time, “the Gospel makes possible an appeal to her freedom precisely by precluding any possibility of judgment by others,” by instead enveloping her in the caring community of the church. On the other hand, the church that fails to defend the victim, but also fails to appeal to the victim’s own agency in Christ the Crucified who forgave his executioners reveals its own captivation by the brave new world of the sovereign self: “a sure sign that we do not believe the Gospel, that we do not really believe that good can come from evil or that the future is open or that there is any wisdom on such matters than the world’s” (59).

A Critical Question in Conclusion

[23] Oehschlaeger is deeply indebted to Stanley Hauerwas, as will be evident to perceptive readers. In the way that Oehlschlaeger appropriates Hauerwas, we should all be his debtors. Yet in this insightful (and for his argumentative posture, I would add, crucial) appeal to Christian liberty, Oehlschlaeger also reveals his debts to Lutheranism. Just here, however, some genuine difficulties arise touching upon the coherence of his proposal. Can he really concede the right to self-defense, as he does in the discussion above of abortion by a victim of rape or incest? In the course of this book, he has given us no other rationale for “defense” than as the ideological masking of Hobbes’ alleged necessity of self-preservation, not really then a Christian possibility at all. Likewise, is the appeal to Christian liberty in fact not subversive (to the point of civil disobedience, itself a form of non-violent coercion) of the kind of sovereignty in terms of which Oehlschlaeger has so insightfully decoded our brave new world of abortion on the way to eugenics, infanticide and cloning? Hobbes certainly thought so! Suppressing Christian liberty (which the Enlightenment called “enthusiasm”) was one of the main responsibilities of Hobbes’ secular sovereign. We are perhaps closer to the catacombs than Oehlschlaeger seems to allow, if in fact the juggernaut of the sovereign self with its brave new world is what this book portrays them to be.

[24] Pray God, there are alternatives. Radical Orthodoxy loves to assimilate Locke to Hobbes, but in fact Locke may be read, especially in his political philosophy, as restoring a new place for Christian liberty under the banner of “toleration” (not the vulgar pluralism of today’s popular culture but exactly the kind of vigorously critical pluralism which Oehlschlaeger assumes in the argumentative posture of this book). In that case, it is possible to think of “defense,” not as the ideological rationalization of Hobbesian aggression, but as a public act of love, as the justice which in a sinful world forcibly intervenes to protect an innocent in danger of life, whether from natural disaster or the aggression of another, even sacrificially to intervene, potentially at the cost of life or limb. That is actually how Luther’s argument from person to public official worked: in both, it is the same self-giving Christian love at work, personally bearing all things, publically risking all things, yet in each case for the sake of others. Wouldn’t this approach to theological ethics limn the legality of abortion in a somewhat different light than laissez-faire abortion on demand? Limiting the question of “defense,” itself little probed as just mentioned, to the limit cases of rape and incest tacitly ignores the vast majority of “convenience” or “bad Samaritan” abortions. Leaving these acts to private and wholly subjective determinations of personal sovereignty in turn masks all sorts of unjust social conditions, not only those of gender inequality, which cry out for prophetic discernment and rebuke. On the other hand, why shouldn’t the state be summoned in principle and in some proportionate way to defend unborn life against the callous disregard for its individuality which Oehlschlaeger has so powerfully vindicated in the pages of this book? As there in fact may be “just war” –more a police action to restore the political work for peace than what traditionally we call “war”—are there not also justifiable abortions? Likewise, as there are in fact unjust wars against which Christians should conscientiously object, with all that entails, might not Christians work politically to change the policy of the state so that it works to inhibit, if not prevent unjust abortions? Indeed, as citizens in, but not subjects of, this brave new world, should they not already now conscientiously object?