[1] The bursting housing bubble and subsequent recession has renewed interest in macroeconomic stabilization policy among economists and non-economists alike. With politicians feeling pressure from constituents, government action appears to be inevitable. Daily newscasts bring word of new policies aimed at curing the nation’s economic woes. The most popular proposals involve boosting aggregate demand through some type of fiscal stimulus.

[2] As Clark and Lawson (2007) point out, economists are “generally reluctant” to address normative questions concerned with “how society should operate.” Instead, they prefer to make positive observations with respect to given ends. Friedman (1953) explains:

Positive economics is in principle independent of any particular ethical position or normative judgments. […] Normative economics and the art of economics, on the other hand, cannot be independent of positive economics. Any policy conclusion necessarily rests on a prediction about the consequences of doing one thing rather than another, a prediction that must be based—implicitly or explicitly—on positive economics (181).

Continuing in the tradition of economic science, I focus exclusively on the positive aspects of fiscal policy intended to smooth business cycle fluctuations.

Considering the economics of fiscal policy[1]

[3] There are two types of fiscal stimuli: spending increases and tax decreases.[2] Spending can be increased through direct government expenditures or by giving individuals money to spend themselves. The former leaves market decisions in the hands of policy makers. Which projects should be undertaken? Who should be hired to complete the project? How much will it cost? These questions must be answered. Unfortunately, the incentives politicians face often lead to inefficiency. Projects are prioritized according to personal agendas. Insiders, with connections to key political players, are picked over outsiders. Since those doing the spending do not bear the cost of the expenditure, waste often results.

[4] Even if a mechanism to circumvent the problem of inefficiency in government action were in place, the productivity of new governmental projects would likely be significantly lower than that of projects already being carried out. This is because the most valuable projects a government could choose to take on—providing roads and bridges, national defense, etc.—have already been selected.

[5] Additionally, there is little reason to imagine that the productivity of a proposed investment project is highly correlated with the current growth rate of the national economy. If efficiency is the evaluative criterion, roads should be repaired when and because they are in sufficiently poor condition, but not simply because the economy is in a slump. When arguments to improve infrastructure are made contingent on the poor performance of the economy, one should question whether the investment’s productivity has even been considered.

[6] Boosting aggregate demand by issuing checks to individuals is also problematic. Stimulus checks are debt-financed, so the government will have to raise taxes (or cut spending) in the future to pay for the expenditure. If individuals realize that today’s spending will be paid for by tomorrow’s taxes, a significant portion of the stimulus will be saved.[3] As a result, stimulus checks have little effect on aggregate demand.

[7] Since tax cuts effectively increase their beneficiaries’ incomes, they function in much the same way as a stimulus check. Therefore, individual tax cuts also suffer from the ‘stimulus saving’ problem. Furthermore, cuts in taxes that are correlated with hours worked (i.e. reducing employee portion of the payroll tax, decreasing income tax rates, etc.) are equivalent to wage increases from the perspective of workers.[4] As a result, the quantity of labor supplied increases. If a surplus of labor (unemployment) already exists, tax cuts to individuals would not be recommended; in fact, they would exacerbate the problem.

[8] Assuming prices are flexible, tax cuts to employers are equivalent to tax cuts to employees. However, there is reason to believe that wages are sticky in the short run.[5] Unable to adjust wages downward, employers lay some workers off while employing others at wages above the equilibrium level. Temporary cuts in the employer portion of payroll taxes would lower the effective hourly wage of workers. By mimicking a perfectly functioning price system, this tax cut is likely to reduce unemployment.

[9] Of the various options offered above, the last one—a temporary cut in the employer portion of payroll taxes—seems to be the most promising with respect to smoothing out the business cycle. But the discussion of fiscal stimuli presented above presupposes the answer to a very important question: is fiscal policy the optimal strategy for dealing with this recession?

Fiscal policy reconsidered

[10] Unfortunately, the desirability of fiscal policy at present is ambiguous. First, it is unclear that the current recession is exceptionally devastating. To be sure, times are tough. Unemployment, reported at 7.2 percent in January, is certainly high by American standards. But in comparison, the European Union averaged roughly 8.5 percent from 1996 to 2006. Furthermore, the current recession does not seem to be uncharacteristic. The US has experienced a recession roughly every ten years since the early 1960s.[6]

[11] Second, fiscal policy will be successful. While basic macroeconomic theory suggests governments can smooth out fluctuations in the business cycle, executing fiscal policy in this capacity is not so easy in the real world. Since timing is crucial, several lags render government action less effective. It takes time to collect macroeconomic data, identify a problem, develop a plan, and implement an agreed upon policy. Even after a policy is put into action, additional time is necessary for it to take effect.[7] Moreover, it is heroically assumed that there are no errors in the process: data collection is accurate; misidentification does not occur; an adequate plan is drafted; and policies are implemented as designed. Realistic assumptions would produce an entirely different result, but one that is more consistent with the historical record.

[12] Consider the Celtic case. Following the 1973 oil shock, the Irish government attempted to boost aggregate demand by implementing expansionary fiscal policies. Public infrastructure projects were taken on; government agencies expanded to offset unemployment; and transfer payments increased. Even still, Ireland’s annual growth rate averaged a paltry 2.2 percent from 1973-1992.

[13] Making matters worse, fiscal expansion resulted in a massive current deficit by 1977. Public sector borrowing rose from 10 to 17 percent of GNP. Lenders began demanding high-risk premiums. Interest rates in Ireland were 15 percent higher than in Germany. In the end, fiscal policies were not only ineffective at stimulating the economy but also left the Irish government with a fiscal crisis.[8]

[14] Finally, many economists believe the potential benefits of short-term macroeconomic policy pale in comparison to the corresponding gains from economic growth. Robert Lucas (1988) remarked that, “Once one starts to think about [economic growth], it is hard to think about anything else.” Why is this the case? Even small changes in average annual growth rates can drastically affect living standards in the long run.

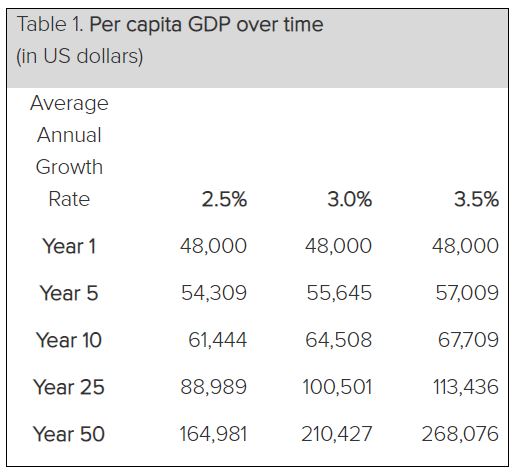

[15] Table 1 illustrates the effect of small differences in real economic growth rates over time for three hypothetical countries. Initial per capita GDP for all three countries is assumed at $48,000 (roughly that of the US in 2008). The middle country, growing at an average annual rate of 3 percent, is comparable to the US at present. While the differences in per capita GDP in years five and ten are fairly small, these differences are compounded over time. By year 25, individuals in the slowest growing country earn approximately $24,447 less than those in the fastest growing country. These results are even more apparent when a longer horizon is considered. In year 50, average incomes in the poorest country are less than two thirds of those in the richest country.

Table 1. Per capita GDP over time

(in US dollars)

[16] These figures should send a clear message to politicians concerned with living standards in their country: focus on growth. When it is realized that short-term stabilization policies could actually harm long-term growth, as in the case of Ireland above, the appeal of fiscal stimuli diminishes further.

Conclusion

[17] While government action can be ethically supported in some situations on consequentialist grounds, the economics of fiscal stimuli do not make for a strong case. The mechanisms for boosting aggregate demand are imprecise and potentially detrimental to long-term growth. Although most would prefer to do something rather than nothing in the face of an economic crisis, it might just be that doing nothing is the best course of action available.

References

Clark, J. R. and Robert A. Lawson. 2007. “To whom does wealth belong? An Economic Perspective.” Journal of Lutheran Ethics, 7(9).

Hall, Joshua C. and William J. Luther. Forthcoming. “Ireland.” Booms and Busts: An Economics Encyclopedia. Mehmet Odekon (ed).

Friedman, Milton. 1953 (reprinted 1970). “The Methodology of Positive Economics.” Essays in Positive Economics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 3-43.

Hazlitt, Henry. 1959 (reprinted in 1995). The Failure of the “New Economics”: An Analysis of the Keynesian Fallacies. Upper Saddle River: Foundation for Economic Education.

Hazlitt, Henry, ed. 1960 (reprinted in 1984). The Critics of Keynesian Economics. New York: University Press of America.

Judge, Rebecca P. 2006. “Economic Perspectives on Ethical Taxation.” Journal of Lutheran Ethics, 6(4).

Lucas, Robert. 1988. “On the Mechanics of Economic Development.” Journal of Monetary Economics 22: 3–42.

Powell, Benjamin. 2003. “The Case of the Celtic Tiger.” Cato Journal, 22.

Endnotes

[1] For criticisms of the framework on which macroeconomic theory is based, see Hazlitt (1959) and (1960).

[2] For a discussion on the ethics of taxation, see Judge (2006).

[3] Some have proposed offering the stimulus in the form of a gift card that expires after a given period of time. Rather than solving the problem, though, this suggestion merely highlights the complexity of human behavior. Given that money is fungible, one could simply make purchases with the stimulus funds while saving other sources of income that would have otherwise been spent. No scheme has been devised as of yet to mitigate the ‘stimulus saving’ problem; nor does it appear than one will be discovered in the near future.

[4] The alternative is to cut taxes by a fixed amount.

[5] While few prices adjust immediately, economists use the term “sticky” to mean that a particular price (in this case, wages) adjusts significantly slower than is common. This turns out to be quite important. Unable to ration via the price mechanism, suppliers resort to rationing by quantity. The latter is typically considered less efficient.

[6] A list of recessions follows: 1960-61, 73-75, 80-82, 90-91, 2001-03.

[7] The effects of fiscal policy are not realized until roughly six months after implementation.

[8] For more on Ireland, see Powell (2003) and Hall and Luther (Forthcoming).