[1] Given the relationship between religion and violence, I want to explore a very controversial claim, namely, that religion is responsible for much of the institutionalized violence that exists in the world. Before examining the truth or falsity of this claim, however, I need to define important concepts including religion and violence, examine the nature of violence, and explore examples of institutionalized violence. I will then conclude by exploring Rene Girard’s excellent evaluation of the claim.

The Reality of Violence

[2] Violence is a widespread reality in our world and few people can deny the role of rhetoric in the instigation of such violence. In many instances institutionalized violence is the product of political struggles that are inspired by lofty or incendiary rhetoric. Those engaged in political rhetoric may seek human liberation or may seek to maintain the status quo. A second type of violence is the product of religious rhetoric. Again the motives may be lofty or destructive.

[3] An important question that arises is which type of rhetoric causes the greater proportion of violence? Mark Jurgensmeyer, a professor of sociology and religion, points to a recent phenomenon that has emerged in response to globalization that has linked religion to political violence. This development has exacerbated and complicated the question, although this may be an ancient problem. Jurgensmeyer noted many instances of violence, from different religious perspectives, in which religious rhetoric played a central role. He cited the following examples. Anti-abortion Christians have murdered physicians and bombed family planning clinics. A Seventh Day Adventist apocalyptic cult in Texas, the Branch Davidians, were engaged in a deadly standoff with Federal Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms agents and an apocalyptic Buddhist cult, known as Aum Shinrikyo, launched a deadly sarin gas attack in the Tokyo subways. Supporters of Messianic Zionism assassinated Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and committed acts of violence against Palestinian Muslims. Islamic fundamentalists bombed the first World Trade Center, and Sikh separatists killed many people in the Punjab region of India.[1] In all of these cases religion has been used as an “aspect of social identity” and as a “political resource for vengeful ideologies.”[2] In all of these cases there appears to be a clear connection between religion and violence. But is such a connection substantiated?

Religion as the Primary Cause?

[4] Many people assume that religion is the primary cause of violence. Adherents of this presupposition can be divided into two groups. While one group is composed of those who believe that religion inherently contributes to violence because of its exclusive worldview, the other group is comprised of those who believe that religion is exploited by opportunists who seek to legitimate their violent endeavors.

[5] There is no denying that religion has historically been used to justify violence. Religious violence has taken a number of forms but I will limit my thoughts here to the topic of war or institutionalized violence. Nowhere is the dynamic between religion and violence more evident than in the Holy War and Just War traditions, dual religious justifications for the use of violence. A careful perusal of the Hebrew Bible shows that violence was justified in the name of God (1 Samuel 15:3). This violence was commonly referred to as a Holy War but biblical scholars refer to it more specifically as the ban or h???rem. In the Torah, calls to war were made by military, political and religious leaders using God as justification (Numbers 21:1-3). During the Middle Ages Pope Urban II launched the first Crusade to re-conquer the holy lands using the same religious Holy War justification. The Spanish theologian Francisco de Vitoria defended the mistreatment of the natives of the Indies, the seizure of their land, the plundering of their goods and resources, and their massacre based on six arguments. These included the notions that the natives were heretics, guilty of mortal sin because of their contumacy and idolatry, unsound of mind, and not the rightful owners of the land they inhabited.[3]

[6] Historians of religion have identified a Just War tradition in one form or another in many religious perspectives throughout history. Not unlike the biblical traditions noted above, Islam also struggles with the challenges arising from religion and the specter of violence. Although the ultimate goal of an Islamic worldview is the attainment of peace, war is understood to be necessary to defend the interests of the community. From this perspective, war is considered a religious duty dependent on the will of God. Human beings are required to submit to the will of God (Islam) and strive (jihad) in pursuit of the divine will.[4]

[7] Islamic jurists have traditionally distinguished between four types of jihad, corresponding metaphorically with heart (the individual’s struggle with evil), tongue (the correction of wrong thinking or evil doers), hands (the correction of wrong thinking or evil doers), and sword (waging war against threats to the community and faith).[5] Furthermore, Contemporary Islamic scholars make a distinction between a greater and a lesser jihad. The greater jihad refers to a person’s internal spiritual struggle to become a better human being, while the smaller jihad refers to acts of combat for purposes of defending one’s community and faith.[6]

[8] Modern proponents of those who assert that religion causes violence can be divided into public intellectuals and academics. Public intellectuals such as Richard Dawkins and Christopher Hitchens have made the claim that religious sentiments breed fanaticism, which in turn leads to institutionalized violence.[7] Although these voices are well publicized by the http://www.elca.org/~/media, their arguments have been found wanting because of their sweeping generalizations and lack of objectivity.

[9] As such, it is better to focus on the work of academics that specialize in the field of religious studies. Charles Kimball, a professor of religion, believes that religion has contributed to more violence than any other institution in human history.[8] Kimball points to five warning signs that predict when a religion is prone to become violent. These include: absolute truth claims, blind obedience, the establishment of an apocalyptic or “ideal” time to act, the belief that the end justifies any means, and a declaration of a Holy War.[9] Kimball’s conclusion is that there are people of “good faith” who could counter-balance the corruptive influences of extremists by looking out for these five warning signs and by living out three cardinal directives. He identifies them as “faith, hope and love.”[10]

Religion Not the Primary Cause of Violence

[10] Critics of this first group of thinkers believe that the problem is much more complex and must take into consideration the human element. Theologians Robert McAfee Brown and William T. Cavanaugh have pointed out that terms such as “religion” and “violence” are misleading and need to be reevaluated. Beginning with the term religion, Cavanaugh points to Wilfred Cantwell Smith’s claim “that in pre-modern Europe there was no significant concept equivalent to what we think of as religion, and furthermore there is ‘no closely equivalent concept in any culture that has not been influenced by the modern West.’”[11] Scholars of religion, most prominently Jonathan Z. Smith, have established that religion is an academic term invented by Western scholars to examine this human phenomenon.[12] As such, the concept means very little outside of academic circles.

[11] A second related problem relates to the challenge of classifying what constitutes a religion or religious practice. The term religion is derived from two Latin words; religare (that which binds) and religio (a constraint which one cannot evade).[13] In other words, religion is a binding concern to which we feel deeply committed. This binding concern was defined by the German-American theologian Paul Tillich as “ultimate concern.” Tillich established that “there are many objects that [human beings] invest with ultimacy, many concerns that they hold with ultimate seriousness.”[14] From this perspective, in cases of “religiously” inspired terrorism” it may be impossible to distinguish between nationalism, political sentiment and confessional commitment, since all can be construed as ultimate concern.

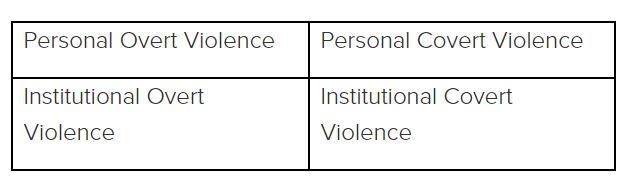

[12] A third problem, relates to the definition of violence and how the term has been applied. The word violence is derived from the Latin violare; to violate, disregard, abuse or deny the personhood of another.[15] Theorists traditionally have interpreted violence too narrowly. Brown identified a continuum containing four manifestations of violence (as demonstrated in the chart below):

[13] The most common form of violence is individual overt violence, in which one individual does physical harm to another individual. When overt physical harm is perpetrated collectively it becomes institutionalized violence. This violence takes the form of war or political repression. Personal covert violence occurs when an individual psychologically harms another individual. Finally, personal covert violence can become institutionalized, when a society systematically violates the personhood of its members.[16] Brown also provides a second overlapping insight regarding violence which he refers to as the spiral of violence. Brown begins by stating that there is a hidden violence that surrounds human beings. Injustice is the most basic form of violence in society and constitutes the first stage of the spiral. Injustice is a hidden covert violence which destroys self-worth and robs human beings of their potential. Over time injustice breeds resentment and contributes to violence. If a society is repressive and becomes overly oppressive, it breeds revolution. This destructive violence is directed at the status quo. Confronted by violent revolt, those who hold power do not remain idle, and revolt is put down by any and all means. Token concessions to the oppressed are made, superficial changes occur, but most likely the status quo retaliates with further repressive measures.[17] Brown believes that modern discussions of violence ignore covert violence. By emphasizing the destructive tendencies in religion, the debate downplays a religion’s role in human liberation and empowerment.[18]

[14] The last point of contention deals with a logical inconsistency in the group that asserts that religion is inherently violent. Cavanaugh believes that Kimball and others create a hierarchy of violence by creating a false dichotomy between secular and religious violence. Kimball concluded that secular violence may be at times necessary, while religious violence is always morally reprehensible.[19] Cavanaugh characterizes this distinction as a dangerous “hierarchization” of violence that subordinates religious violence to secular violence. Kimball’s hierarchy of violence also legitimates state sponsored violence under the guise of Just War, and justifies Western action while demonizing the actions of the other (vis-à-vis Islam).[20]

Girard on Violence and Religion

[15] Rene Girard’s article Violence and Religion: Cause or Effect, presents an interesting perspective on the connection between religion and violence. Girard fleshes out the debate by looking at diverse religious expressions historically and theologically, by comparing them to secular trends, and by drawing interpretative deductions. His final conclusion is that religion has been used as a scapegoat for human violence and is not a reflection of religious sentiment.

[16] Girard, an emeritus Professor at Stanford University, established that violence is a human problem rather than a religious one. Human violence, unlike animal violence which is based on aggression, is caused by desire and competition. Girard argues that all ancient societies are characterized by mimetic rivalry and violence. “Mimesis” which draws its meaning from imitation, establishes that all human beings desire and aspire to possess what other human beings have. Mimetic rivalries take shape and spread like a contagion across groups, leading to instability and inter-group violence.[21]

[17] Girard claims that all “archaic” religions and societies are grounded in foundational myths of an original murder, re-enacted ritually to keep the peace and control violence:

Communities deliberately reproduce these phenomena in their sacrificial rites, hoping in this way to protect themselves from their own violence by diverting it onto the expendable victims, human or animal, whose deaths will not cause violence or rebound because no one will bother to avenge them.[22]

[18] Far from promoting violence, Girard established that archaic religions protected the community from violence. Finally, Girard points out that modern society has evolved in the direction of less and less violence, has championed the protection of victims, and has instituted legal prescriptions to eliminate violent acts.[23] And yet a paradox has resulted from this modern emphasis on defending the victim, namely, there has been an increase in violence and the threat of violence. Coupled with the loss of sacrificial violence, this paradox has contributed to an “unleashing of mimetic rivalries.”[24] Religion is ultimately a scapegoat of mimetic rivalries and the propensity of human beings to act violently towards each other.

Conclusion

[19] Over a hundred years ago Hindu Swami Vivekananda made a sober assessment of the American religious landscape:

No other human interest has deluged the world in so much blood as religion; at the same time nothing has built so many hospitals and asylums for the poor… as religion. Nothing makes us so cruel as religion, nothing makes us so tender.[25]

[20] What Vivekananda makes clear here is that individuals through their actions can affirm life and human dignity or destroy life and community. In other words, religion can be used as a force for good but unfortunately is quite often misused with disastrous consequences. Mark Jurgensmeyer concludes that there are marginal elements in every religion that interpret the tradition at the most fundamental level relative to other members of their society. These elements struggle with moderate elements in their society who they believe have accommodated themselves to the corruptive influences of modernity and globalization. Jurgensmeyer explains religious terrorism as an attempt to send a message to perceived enemies of their faith. But, ultimately religion provides a liberating element. He concludes:

This is one of history’s ironies, that although religion has been used to justify violence, violence can also empower religion. Perhaps understandably, therefore, in the wake of secularism…religion has made its reappearance as an ideology of social order in a dramatic fashion: violently. In time the violence will end, but the point will remain, Religion gives spirit to public life and provides a beacon for moral order. [26]

NOTES

[1] Mark Jurgensmeyer, Terror in the Mind of God: The Global Rise of Religious Violence, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2000.

[2] Ibíd., p. xi.

[3] Francisco de Vitoria, De Indis et De Jure Belli Relectiones, Buffalo: NY, W.S. Hein, 1995, De Indis, Section II, paragraph 16.

[4] Richard C. Martin, “The Religious Foundations of War, Peace, and Statecraft in Islam,” in Just War and Jihad, edited by John Kelsay and James Turner Johnson (New York: Greenwood Press, 1991), pp. 91 & 107.

[5] John Ferguson, War and Peace in the World’s Religions (London: Sheldon Press, 1977), p. 130.

[6] As’d Abu Khalil, Bin Laden, Islam and America’s New War on Terror, New York: Seven Stories Press, 2002, p. 28. Cf., Abdulaziz Sachedina, Justifications for Violence in Islam, Journal of Lutheran Ethics, February 19, 2003.

[7] Richard Dawkins, The God Delusion, New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2006; Christopher Hitchens, God Is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything, Boston: Twelve Books, 2007.

[8] Charles Kimball, When Religion Becomes Evil, San Francisco: Harper San Francisco, 2002, p. 1. Cf., Richard E. Wentz, Why People Do Bad Things in the Name of Religion, Atlanta: Mercer University Press, 1993; Martin Marty, Politics, Religion, and the Common Good, San Francisco: Jossey Bass, 2000; Lloyd Steffen, The Demonic Turn: The Power of Religion to Inspire and Restrain Violence, Cleveland: OH, The Pilgrim Press, 2003.

[9] Kimball, chapters 2 through 6.

[10] Ibid, pp. 186-195.

[11] Wilfred Cantwell Smith, The Meaning and End of Religion, New York: Macmillan, 1962, p. 19. Cited by William T. Cavanaugh, Sins of Omission: What Religion and Violence Arguments Ignore, The Hedgehog Review, Vol. 6:1, Spring 2004, p. 37.

[12] Jonathan Z. Smith, Imagining Religion: From Babylon to Jonestown, Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1982, p. xi.

[13] Robert McAfee Brown, Religion and Violence, Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1973, 3.

[14] Ibid., p. 4.

[15] Ibid., p. 7.

[16] Ibid., pp. 7-8.

[17] Ibid., pp. 8-12.

[18] See chapter 7 The Religious Community: Resources and Roles.

[19] Cavanaugh, p. 47.

[20] Ibid., p. 47.

[21] Rene Girard, Sacrifice: Breakthrough in Mimetic Theory, East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University, 2011, p. 63.

[22] Ibid., p. X.

[23] Girard, Violence and Religion, pp. 17-18.

[24] Ibid., p. 19.

[25] Diana Eck, A New Religious America, New York: Harper San Francisco, 2001, p.8

[26] Jurgensmeyer, pp. 242-243