[1] Heavy reliance on fossil fuels (coal, oil, and natural gas) together with ecologically damaging land use patterns have produced grave threats to justice, peace, and the integrity of creation. The related challenges posed by global warming and climate change are unprecedented in human history. The first half of this paper summarizes recent scientific findings about global warming and identifies specific ways climate change imperils human rights around the world. The second half of this paper explores two different proposals for securing human rights which address intra-generational ethical issues related to global climate change.[1]

Climate Science

[2] After nearly two decades of intensive study, scientists have reached a much greater consensus about the causes and likely impacts of global climate change. The United Nations established the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in 1988 to review and assess the most recent scientific, technical and socio-economic information relevant to climate change. The IPCC has issued reports every five years and issued its Fourth Assessment Report in four installments during 2007. Over 1,200 authors contributed to the report and their work was reviewed by more than 2,500 scientific experts.[2] Since each report for policy makers is approved line by line in plenary sessions, the IPCC’s findings are arguably the least controversial and most accepted assessments of climate change in the scientific community.

[3] The IPCC states in its Fourth Assessment Report that it has very high confidence [greater than 90 percent probability] that “the globally averaged net effect of human activities since 1750 has been one of warming.”[3] The report demonstrates that global atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide have substantially increased as a result of human activities. For example, the global atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide, the most important greenhouse gas, has increased from a pre-industrial value of about 280 p.p.m. to 379 p.p.m. in 2005. The growing atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide “exceeds by far the natural range over the last 650,000 years (180 to 300 p.p.m.) as determined from ice cores.”[4]

[4] Direct scientific observations of climate change lead the IPCC to declare that warming of the climate system is “unequivocal.” It notes that “eleven of the last twelve years (1995-2006) rank among the 12 warmest years in the instrumental record of global surface temperature.” The IPCC also identifies “numerous long-term changes in Arctic temperatures and ice, widespread changes in precipitation amounts, ocean salinity, wind patterns and aspects of extreme weather including droughts, heavy precipitation, heat waves and the intensity of tropical cyclones.”[5]

[5] These key findings lead the IPCC to the following conclusion. If the world takes a business-as-usual approach and continues a fossil fuel-intensive energy path during the 21st century, the IPCC projects current concentrations of greenhouse gases could more than quadruple by the year 2100. Under this scenario, global-average surface temperature will increase 4.0º Celsius (7.2º Fahrenheit) by the end of the 21st century. Put into perspective, the global-average surface temperature only increased 0.6ºC (1.1ºF) during the 20th century.[6] In a report issued after the IPCC released its Fourth Assessment Report, the U.S. Climate Change Science Program warned “[w]e are very likely to experience a faster rate of climate change in the next 100 years than has been seen over the past 10,000 years.”[7]

[6] This rapid rate of global warming will raise sea levels, endangering millions living in low-lying areas, despoil freshwater resources for one sixth of the world’s population, widen the range of infectious diseases like malaria, reduce global agricultural production, and increase the risk of extinction for 20-30 percent of all surveyed plant and animal species.[8] The IPCC emphasizes that poor communities will be “especially vulnerable” to increasing climate change, “in particular those concentrated in high-risk areas” who “have more limited adaptive capacities, and are more dependent on climate-sensitive resources such as local water and food supplies.”[9]

Climate Change and Human Rights

[7] Given this warning, it should come as no surprise that some poor and vulnerable communities around the world are beginning to argue that climate change is resulting in violations of their human rights. In December 2005 over sixty Inuit Indians who live in arctic regions of the United States and Canada submitted a petition to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. Faced with a rate of warming that is almost twice the pace experienced elsewhere on the planet, the petitioners requested relief “from human rights violations resulting from the impacts of global warming and climate change caused by acts and omissions of the United States.”[10]

[8] This consultation has been convened to celebrate the 60th anniversary of the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948.[11] Drafted originally to protect human dignity after the ravages of World War II, there are several articles in the Universal Declaration which can be applied directly to perils posed by global climate change. Excerpted below are articles in the Declaration which are most clearly relevant:

Article 3

Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of person.

Article 7

All are equal before the law and are entitled without any discrimination to equal protection of the law. All are entitled to equal protection against any discrimination in violation of this Declaration and against any incitement to such discrimination.

Article 12

No one shall be subjected to arbitrary interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence…. Everyone has the right to the protection of the law against such interference or attacks.

Article 17

Everyone has the right to own property alone as well as in association with others. No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his property.

Article 22

Everyone, as a member of society, has the right to social security and is entitled to realization, through national effort and international co-operation and in accordance with the organization and resources of each State, of the economic, social and cultural rights indispensable for his dignity and the free development of his personality.

Article 25

Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond his control.

Article 28

Everyone is entitled to a social and international order in which the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration can be fully realized.

[9] Most nations of the world have endorsed the Universal Declaration on Human Rights, and approximately 75 percent have ratified other legally binding international laws like the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR).[12] The Inuit Indians appeal to both of these international laws in their petition to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. The Inuits also appeal to other legally binding agreements. For example, the Inuits argue that the United States as a member of the Organization of American States must respect their rights under the American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man. They also argue that, as a signatory of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, the United States has committed to developing and implementing policies aimed at reducing its greenhouse gas emissions.[13] The following quote from the Inuit petition summarizes their argument:

The impacts of climate change, caused by acts and omissions by the United States, violate the Inuit’s fundamental human rights protected by the American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man and other international instruments. These include their rights to the benefits of culture, to property, to the preservation of health, life, physical integrity, security, and a means of subsistence, and to residence, movement, and inviolability of the home.[14]

[10] Nearly three years later, the Inuit case remains pending before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. While it is clear that human rights enshrined in various laws appear to be jeopardized by global climate change, this does not mean the Inuits (or others) will prevail in their legal cases. Since climate change is a global phenomenon it is difficult to establish which entities have jurisdiction and authority to rule in any particular case. In addition, courts find it difficult to assign proportional national or corporate responsibility for the greenhouse gases that have been emitted since the advent of the Industrial Revolution.

[11] Legal matters aside, a strong moral argument can be made that global climate change is causing human rights violations.[15] In 2000 the World Council of Churches issued a statement that “equitable rights to the atmosphere as a global commons must be the foundation of proposals to address climate change.”[16] Michael Northcott, author of A Moral Climate: The Ethics of Global Warming, discourages appeals to rights language in Christian responses to climate change.[17] In a recent paper Northcott argues on pragmatic grounds that “it is not the poor or the weak but the powerful who have most successfully mobilized rights claims in the law courts and economic markets.”[18] Moreover, Northcott claims “[t]he assertion of such rights lacks any theological or confessional base in the historic documents of the Christian tradition. More worryingly rights assertions are a foundational source of violence in the history of the modern world.”[19] Northcott argues that throughout Christian history “the ways in which [Christian] communities exercise moral claims on one another have not traditionally been through the language of rights arising from rights or property claims but from obligations recognized in the law of love.”[20]

[12] Are appeals to human rights grounded in the norm of justice incompatible with or less important than moral obligations rooted in the norm of love? I think this is a false dichotomy.[21] Rights, in part, specify the content of our moral obligations to others and thus are an invaluable ethical category, particularly for grounding the moral and legal worth of all forms of life. Obligations imply that we owe something to others and, at least, what we owe them are their rights. The problem with a benevolence and duties-based approach is that duties arise from within and rights can only be requested, whereas in a justice and rights-based approach duties arise in response to those who are demanding their rights. The fact that rights-based appeals have been abused by the powerful does not change the fact that the concept of rights has been at the heart of successful attempts to achieve greater measures of freedom and equality around the world. While a rights-based approach to ethics can accentuate individualism and undermine community, this would be a distorted understanding of the mutual rights and responsibilities of members in a democratic society. Properly understood, a rights-based approach has the best potential for holding together the twin objectives of protecting individuals and the common good because the purpose of rights is to foster relationality rather than undermine it.[22]

Rights-Based Approaches to Climate Policy

[13] Two organizations have recently proposed a rights-based approach to climate policy in order to protect the interests of poor and vulnerable people in the United States and around the world. Both address issues related to intra-generational justice. That is, how should burdens associated with addressing climate change be distributed fairly among present generations, and how might benefits be distributed so that vulnerable people are protected from violations of their human rights?

[14] In September 2007 representatives of the Stockholm Environmental Institute and EcoEquity, a think tank devoted to developing “a just and adequate solution to the climate crisis,”[23] published online The Right to Development in a Climate Constrained World: The Greenhouse Development Rights Framework.[24] Financial support for this project was provided by the large British relief and development organization, Christian Aid,[25] as well as the Heinrich Böll Foundation in Germany, which strives “to promote democracy, civil society, human rights, international understanding and a healthy environment internationally.”[26] In an official statement issued on the tenth anniversary of the Kyoto Protocol, the Executive Committee of the World Council of Churches encouraged “further deliberations and negotiations” about “Greenhouse Development Rights” as the international community develops an agreement to replace the Kyoto Protocol when it expires in 2012.[27]

[15] The authors of The Greenhouse Development Rights (GDR) framework address the impasse which exists between wealthy developed countries and poor developing countries about how to develop an emergency climate stabilization program that will keep global warming under 2º Celsius (3.6º Fahrenheit) by the end of the 21st century. While developed nations that ratified the Kyoto Protocol have begun to take some responsibility for reducing greenhouse gas emissions, developing nations like China, India, and Brazil have refused to accept binding greenhouse gas emission reductions that might constrain their ability to develop and improve the standard of living of their citizens. The GDR framework seeks to overcome this impasse by holding global warming below 2º C “while also safeguarding the right of all people around the world to reach a dignified level of sustainable human development.”[28]

[16] The authors emphasize that this right to development belongs to people within nations and not to nations as a whole. Accordingly, the GDR framework utilizes a “development threshold” based on annual personal income to allocate burden sharing associated with reducing greenhouse gas emissions and increasing sustainable human development. Individuals who fall below this threshold “are not expected to share the burden of mitigating the climate problem,” but those above the development threshold “must bear the costs of not only curbing the emissions associated with their own consumption, but also of ensuring that, as those below the threshold rise toward and then above it, they are able to do so along sustainable, low-emission paths.”[29] The authors of the GDR framework stress, however, that “it should be poor individuals, not poor nations, who are excused from bearing climate-related obligations.”[30]

[17] Since international efforts to grapple with climate change have focused on the obligations of nations, the GDR framework utilizes a “Responsibility and Capacity Index” to translate individual responsibility to national responsibility. The GDR framework defines national capacity as the amount by which a country’s per capita income exceeds the development threshold. Thus, “the portion of a country’s GDP that [falls] below the development threshold would be exempt from being ‘taxed’ to pay for the global emergency program.”[31] The GDR framework utilizes the “polluter-pays” principle to define national responsibility on the basis of “cumulative per capita CO2 emissions from fossil fuel consumption since 1990.”[32]

[18] A revised version of the GDR framework was published in June 2008.[33] In this revision the development threshold is lowered from $9,000 per person (calculated on the basis of purchasing power parity) to $7,500 per person, which is equivalent to $20 per day. On the basis of this development threshold the following graphs indicate how national capacity for responding to the climate and development crises should be fairly allocated among India, China, and the United States.[34] With approximately 95 percent of their population living below the development threshold, the national capacity of India is very small compared to the huge capacity of citizens of the United States which has less than 5 percent of its citizens living below the development threshold.

GDR Framework

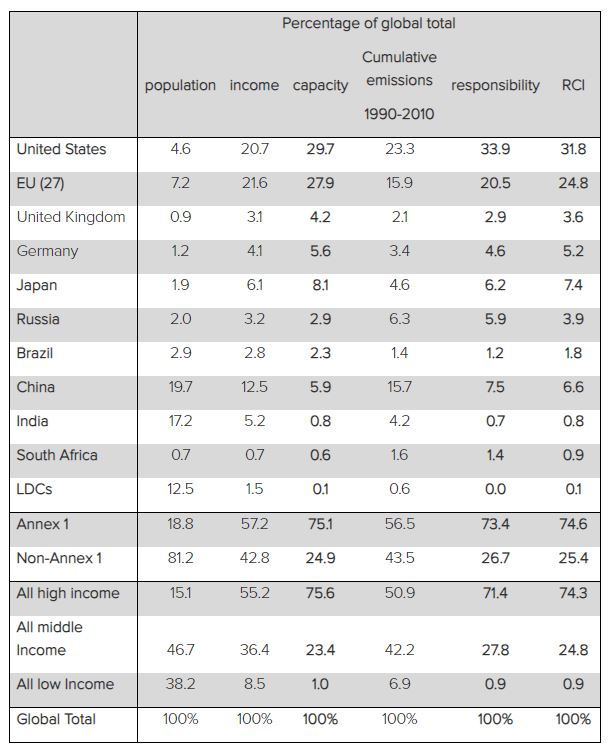

[19] The table below calculates national responsibility for cumulative per capita CO2 emissions since 1990 and combines this with national capacity to arrive at a “Responsibility-Capacity Index” for individual nations and groups of nations.

Percentage of global total

Percentage shares of total global population, income, capacity, cumulative emissions, responsibility, and RCI for selected countries and groups of countries. Based on projected emissions and income through 2010. High, Middle and Low Income categories are based on World Bank definitions.

[20] The authors of the Greenhouse Development Rights Framework argue that the “Responsibility-Capacity Index” (RCI) offers a way for nations to fairly determine their “common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities” under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.[35] Viewed through the lens of the RCI, the United States shoulders 31.8 percent of total global responsibility, and the nations that comprise the European Union bear 24.8 percent of responsibility, but “the wealthy and consuming classes” in developing nations like China, India, Brazil, and South Africa together bear a little more than 10 percent of responsibility as well.[36] The authors argue that the GDR framework, or a similar approach, is the only realistic way to forge the international consensus which will be necessary to hold global warming to 2º Celsius while also securing the right to development for people who are poor.

[21] In July 2008, one month after the revised Greenhouse Development Rights framework was published, the Environmental Justice and Climate Change Initiative released A Climate of Change: African Americans, Global Warming, and a Just Climate Policy for the United States.[37] This study was a collaborative project between leaders of the environmental justice movement in the United States and Redefining Progress, a think tank dedicated to developing “solutions that ensure a sustainable and equitable world for future generations.”[38] The study also frames climate policy within the context of human rights:

Climate change is not only an issue of the environment; it is also an issue of justice and human rights, one that dangerously intersects race and class. All over the world people of color, Indigenous Peoples and low-income communities bear disproportionate burdens from climate change itself, from ill-designed policies to prevent it, and from side effects of the energy systems that cause it.[39]

[22] Since African Americans are one of the largest minority populations in the United States, the bulk of the study focuses on how African Americans are adversely impacted by various issues related to climate change. Separate chapters address health issues related to warming and natural disasters resulting from increased storm intensity, economic impacts associated with rising energy prices and the cost to maintain U.S. energy supplies, and also various dimensions of the persistent phenomenon of institutionalized racism. What follows are key findings excerpted directly from the study’s executive summary:

“Global warming amplifies nearly all existing inequalities….

Sound global warming policy is also economic and racial justice policy….

Climate policies that best serve African Americans and other disproportionately affected communities also best serve global economic and environmental justice….

A distinctive African American voice is critical for climate justice.”[40]

[23] All of these findings are addressed to some extent in the sixth chapter of the report, “Elements of a Just Climate Policy.” Here the authors assess three different climate policy scenarios and variations within them. Where the GDR framework focuses more on how the burden of reducing greenhouse gas emissions should be distributed fairly while preserving the right to sustainable development, the Environmental Justice and Climate Change Initiative focuses on how different climate policies impact and can most benefit people who are poor and the victims of racism.

[24] First, they dismiss “phony reductions” achieved through the European Union Emissions Trading System and the Kyoto Protocol’s Clean Development Mechanism because both have sanctioned continued investments in fossil fuel infrastructure, ecologically damaging hydroelectric projects, and large tree plantations which jeopardize the livelihoods of local communities. They also repudiate carbon offset purchases by rich nations from projects in poor nations because these offsets allow rich nations not to curb their own consumption of fossil fuels. While the authors acknowledge that these policies offer a means to transfer money and technology to developing nations, and also to protect the habitat of endangered species, they argue that these policies are currently too flawed to achieve these goods and actually result in “phony reductions.”

[25] The Environmental Justice and Climate Change Initiative also repudiates “corporate windfalls” associated with “cap-and-trade” systems where greenhouse gas emission allowances are distributed for free by a government agency to corporate polluters. Instead of requiring polluters to pay for the pollution they emit, the free distribution of allowances rewards the polluters and enables only them to benefit financially from the trade of emission allowances. In this approach to climate policy “big polluters are treated as though they have a right to pollute and taxpayers and consumers are obligated to bribe them to quit.”[41] The authors of the study argue that “cap-and-trade” systems of this sort require the long and complex task of determining baseline emission levels for thousands of polluters and the costly task of verifying emissions reductions at thousands of locations. They also worry that powerful corporations will figure out how to “game” the system both in terms of setting the initial emissions cap and also in terms of how the emission allowances will be allocated. Finally, the report emphasizes that “cap-and-trade” approaches can produce emissions “hot spots” where emissions are concentrated disproportionately in communities of color.[42]

[26] The approach to climate policy most favored by the Environmental Justice Climate Change Initiative is oriented around the “polluter-pays” principle. Here the authors explore four different options and emphasize that revenue raised from polluters via any of these options needs to be returned to consumers directly and especially to people who are poor.

[27] The first two options focus on governments imposing a fee or a tax on greenhouse gas emissions.[43] Here the goal is to capture environmental costs associated with greenhouse gas emissions in the prices of goods whose consumption results in emissions. Since a fee or a tax sets a fixed price for emissions, this predictability would help consumers and businesses make better long-range decisions about the costs and benefits of less-polluting technologies. In addition, all consumers and businesses are used to the assessment of separate fees or taxes on various kinds of economic activity and thus a new emissions fee or tax would not be hard to understand. These two strengths are matched by two significant weaknesses. The first is that few politicians are willing to propose new taxes, and many members of the public perceive new fees simply to be taxes under a different name. The second major weakness is that a fee or tax on greenhouse gas emissions does not guarantee that greenhouse gas emissions will be capped at a certain level, and a fee or tax will likely have to be significant in order for emissions to be reduced. For example, it was not until gasoline prices more than doubled between 2006 and 2008 that drivers in the United States began to reduce their vehicle miles traveled. Sadly the revenue from this “tax” was sent to oil-exporting nations; it was not captured by the U.S. government to encourage research and development of alternative fuels or to address the regressive impact of these higher energy costs on people who are poor.

[28] The other two options considered by the Environmental Climate Change Initiative revolve around governments establishing a firm cap on greenhouse gas emissions and then selling related emission allowances. In one case emission allowances are auctioned to polluters by government; in the other case emission allowances are distributed for free by government to citizens who then sell them directly to polluters. The study refers to the former as a “cap-and-auction” approach and to the latter as a “cap-and-dividend” approach. In both cases “collective ownership of the atmospheric commons” is viewed as “a shared birthright” for all people on the planet in contrast to the “cap-and-trade” approach “where polluting is a right that belongs to the polluter.”[44] In both cases the more a company pollutes, the more it will have to pay for the necessary emissions allowances. A key weakness associated with the “cap-and-auction” approach is that auction prices could vary significantly in relationship to demand. While the study indicates how this problem could be addressed, corporations would still pass these costs on to consumers and these costs would hit the poor the hardest. A key weakness associated with the “cap-and-dividend” approach is that it would be difficult to empower all citizens equally to sell the emission allowances allocated to them and it would likely result in high administrative expenses.

[29] Regardless which route to climate policy is taken, the Environmental Justice and Climate Change Initiative advocates a “Climate Asset Plan,” which is designed not only to provide “climate justice” but also “common justice, justice for all.”[45] One way to approach these goals would be to distribute government revenues raised by fee, tax, or auction on an equal per capita basis. The authors of the study note that this approach would yield a disproportionate benefit to African Americans and others who are poor because the payment would represent a larger percentage of income for low-income households. Nevertheless, the authors argue that “a more nuanced approach may allow us to reap even larger benefits for justice, the economy, and African Americans.”[46][46] They endorse distributing 62 percent of the emissions revenue on a per-capita basis to all citizens, but they propose allocating an additional 18 percent for energy assistance programs like the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program, and the remaining 20 percent to promote energy efficiency.

[30] There are certainly many weaknesses associated with the approaches to climate policy advocated by the Greenhouse Development Rights framework and the Environmental Justice and Climate Change Initiative. Indeed, many will view them as unrealistic. I prefer to view them as moral correctives to policy discussions that too quickly and easily discount the interests and voices of people who are poor and disenfranchised. I agree that legal attempts to seek redress for the violations of human rights caused by global climate change will likely flounder. As a Christian ethicist, however, I think moral appeals to human rights concerns are essential as nation states and the international community come to grips with the unprecedented perils posed by global warming and climate change.

Endnotes

[1] I am also working on a second paper that addresses inter-generational ethical issues related to global climate change. That paper attempts to develop ethical criteria to assess the adequacy of various climate policy proposals.

[2] Intergovernmental Panel of Climate Change, “Fact Sheet for “Climate Change 2007,” http://www.ipcc.ch/press/ar4-factsheet1.htm

[3] Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Fourth Assessment Report: The Physical Science Basis (Geneva: IPCC Secretariat, February 2007), 2-3, http://www.ipcc.ch/ipccreports/ar4-wg1.htm

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid., 4-6.

[6] Ibid. This mean projection is for the fossil fuel-intensive A1F1 scenario, the worst of the six developed by the IPCC. Under this scenario greenhouse gas concentrations are projected to increase from approximately 430 ppm of carbon dioxide equivalent (C02e) in 2005 to 1550 p.p.m. C02e by 2100. Even under the IPCC’s best case scenario (B1) greenhouse gas concentrations increase to 600 ppm C02e by 2100, which they estimate will lead to a warming of 3.2ºF by the end of this century—almost three times the rate of warming over the past 100 years.

[7] U.S. Climate Change Science Program, The Effects of Climate Change on Agriculture, Land Resources, Water Resources, and Biodiversity (September 2007 public review draft), 7, http://www.climatescience.gov/Library/sap/sap4-3/public-review-draft/sap4-3prd-all.pdf.

[8] Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Fourth Assessment Report: Climate Change Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability (Geneva: IPCC Secretariat, April 2007), 8, http://www.ipcc.ch/ipccreports/ar4-wg2.htm.

[9] Ibid.

[10]Inuit 2005, “Petition to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights Seeking Relief from Violations Resulting from Global Warming Caused by Acts and Omission of the United States,” p. 1, http://www.inuitcircumpolar.com/files/uploads/icc-files/FINALPetitionSummary.pdf. Cited in James Peter Louviere and Donald A. Brown, “The Significance of Understanding Inadequate National Climate Change Programs as Human Rights Violations,” http://climateethics.org/?p=39.

[11] United Nations, “Universal Declaration of Human Rights,” http://www.un.org/Overview/rights.html.

[12] James Peter Louviere and Donald A. Brown, “The Significance of Understanding Inadequate National Climate Change Programs as Human Rights Violations,” http://climateethics.org/?p=39.

[13] Inuit 2005, “Petition to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights Seeking Relief from Violations Resulting from Global Warming Caused by Acts and Omission of the United States,” 5.

[14] Ibid.

[15] See Donald Brown, “The Case for Understanding Inadequate Climate Change Strategies as Human Rights Violations,” in L. Westra, K. Bosselmann and R. Westra eds, Reconciling Human Existence with Ecological Integrity, Earthscan Publications, 2008.

[16] World Council of Churches, “The Atmosphere as Global Commons: Responsible Caring and Equitable Sharing: A Justice Statement regarding Climate Change from the World Council of Churches,” http://www.wcc-coe.org/wcc/what/jpc/cop6-e.html.

[17] Michael Northcott, A Moral Climate: The Ethics of Global Warming, Orbis Books, 2007.

[18] Michael Northcott, “Apocalypse, Accountability, and Climate Change,” 12, an unpublished paper written for a theological consultation on climate change convened by the Lutheran World Federation in Geneva, Switzerland, October 2-4, 2008.

[19] Ibid., 13.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Here I draw on the work of James A. Nash who develops a rights-based approach to environmental ethics in Loving Nature: Ecological Integrity and Christian Responsibility, Abingdon Press, 1991.

[22] James A. Nash makes this point in “Human Rights and the Environment: New Challenges for Ethics,” Theology and Public Policy, Vol. 4, No. 2, Fall 1992, 45.

[23] See http://www.ecoequity.org/about.html.

[24] Paul Baer, Tom Athanasiou, and Sivan Kartha, The Right to Development in a Climate Constrained World: The Greenhouse Development Rights Framework, Heinrich Böll Foundation, 2007. See http://www.ecoequity.org/docs/TheGDRsFramework.pdf.

[25] See http://www.christian-aid.org.uk/.

[26] See http://www.boell.org/overview.asp.

[27] See http://www.oikoumene.org/en/resources/documents/executive-committee/etchmiadzin-september-2007/28-09-07-statement-on-the-10th-anniversary-of-the-kyoto-protocol.html. Michael Northcott refers to this statement in his unpublished paper.

[28] Paul Baer, Tom Athanasiou, and Sivan Kartha, The Right to Development in a Climate Constrained World: The Greenhouse Development Rights Framework, 9.

[29] Ibid., 16.

[30] Ibid., 29.

[31] Ibid., 31.

[32] Ibid., 38.

[33] See http://www.ecoequity.org/GDRs/GDRs_ExecSummary.html.

[34] Ibid.

[35] See http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/convkp/conveng.pdf.

[36] See http://www.ecoequity.org/GDRs/GDRs_ExecSummary.html.

[37] J. Andrew Hoerner and Nia Robinson, A Climate of Change: African Americans, Global Warming, and a Just Climate Policy for the U.S., Environmental Justice and Climate Change Initiative, 2008. See http://www.ejcc.org/climateofchange.pdf.

[38] See http://www.rprogress.org/about_us/about_us.htm.

[39] J. Andrew Hoerner and Nia Robinson, A Climate of Change: African Americans, Global Warming, and a Just Climate Policy for the U.S., 1.

[40] Ibid.

[41] Ibid., 46

[42] Ibid., 47.

[43] Ibid., 48.

[44] Ibid., 49.

[45] Ibid., 51.

[46] Ibid., 50.